Home Others Artificial Intelligence The GAIN AI Act: Is America Go...

The GAIN AI Act: Is America Going Rogue on Semiconductors?

Artificial Intelligence

Business Fortune

02 October, 2025

Semiconductors are a hot topic in Europe, but even more so across the Atlantic. While Trump managed to strong-arm the Europeans into signing a trade deal that introduces new tariffs and obliges them to purchase $40 billion worth of American semiconductors, a new piece of US legislation could well undermine this push to make Europe more dependent on American chips. This erratic, uncooperative policymaking on the U.S. side should only reinforce ongoing European efforts at strategic tech sovereignty.

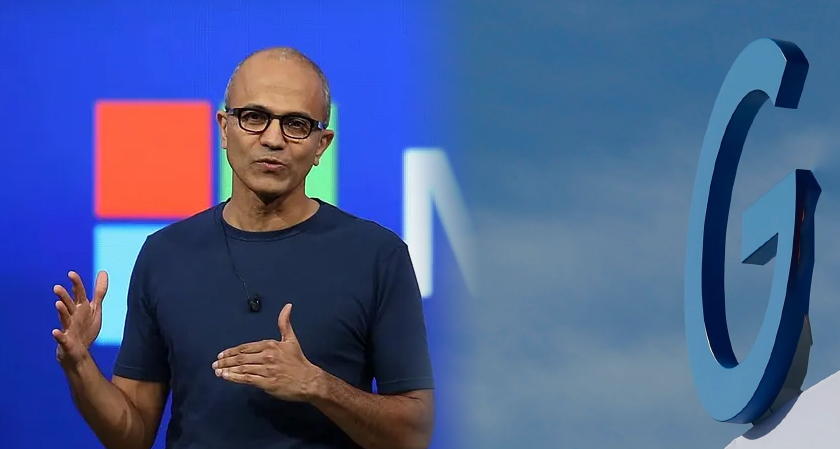

In an unanticipated move, the US Senate is currently working on a bill requiring American companies to prioritise sales of their products to domestic entities. This GAIN AI Act (Access and Innovation for National Artificial Intelligence Act) aims to secure US leadership in the field of artificial intelligence. Such a measure comes at the expense of free trade, of allied countries, and even of the Trump administration’s declared intention to increase Europe’s reliance on U.S. semiconductors, much to the dismay of U.S. tech giants like Nvidia. Such contrarian legislative behaviour once again destabilises global tech markets and suggests Washington is sinking into schizophrenia, once again underlining the crucial need for Europe to achieve sovereignty in such an essential sector.

GAIN AI Act proposed amid contradictions in trade strategy

The U.S. Senate has introduced the Guaranteeing Access and Innovation for National Artificial Intelligence Act of 2025 (GAIN AI Act) as part of the annual National Defence Authorisation Act. At the core of this legislation is a requirement that American AI chipmakers give U.S. buyers, especially small businesses, start-ups and universities, the "first option" to purchase advanced AI GPUs, before any overseas entities, including allies in Europe or countries of concern like China.

To enforce this, the bill would impose performance-based export controls: GPUs with a total processing performance (TPP) of 4,800 or above would be outright barred from external sale. These thresholds are applied even to older models. For example, Nvidia’s H100 or AMD’s Instinct MI308 would fall under these restrictions. Export licences would be denied if U.S. orders are unmet, if pricing advantages are extended to foreign buyers, or if there is any risk that exports could help non-U.S. competitors.

Some voices in the U.S. have lauded the move. Brad Carson, President of Americans for Responsible Innovation (API) stated: “Advanced AI chips are the jet engine that’s going to enable the U.S. AI industry to lead for the next decade. Globally, these chips are currently supply-constrained, which means that every advanced chip sold abroad is a chip the U.S. can’t use to accelerate American R&D and economic growth. As we compete to lead on this dual-use technology, including the GAIN AI Act in the NDAA would be a major win for US economic competitiveness and national security.”

Industry voices, on the other hand, have been scathing in their response. One Nvidia spokesperson stated: "The AI Diffusion Rule was a self-defeating policy, based on doomer science fiction, and should not be revived. Our sales to customers worldwide do not deprive U.S. customers of anything — and in fact expand the market for many U.S. businesses and industries.” The firm contends that prioritising national demand is unnecessary and would harm global competition and U.S. technological leadership.

But most concerning for European allies, is how this legislative move represents a deep-seated instability within American politics that can have far-reaching consequences on global trade, and trust between allies. This emerging export-restrictive policy arrives even as the Trump administration had recently secured a deal compelling Europe to buy $40 billion worth of American semiconductors. Does this mean that the U.S. will simply shelve export agreements when convenient?

Will Europe now turn inward?

Although some European policymakers and industry players may perceive this isolationist move by the U.S. as a kick in the teeth, others may recognise a real opportunity. For Europe has been striving for some time to decouple itself from an over-reliance on U.S. and Asian tech markets in order to reinforce European resilience to global market instability. The European Chips Act for example, adopted in late 2023, committed around €43 billion in public and policy-driven investment with the aim of raising the EU’s share of global chip production from under 10% to 20% by 2030.

This act rests on three pillars: fostering R&D and innovation, enabling state-aid-backed semiconductor manufacturing, and monitoring supply chains to ensure resilience. Though signalled with great ambition, the roll-out has been slower than hoped, constrained by bureaucratic complexity and partial reliance on redirected EU funds rather than entirely new money. In reality, the EU is playing a balancing act as it seeks further autonomy, as the process is gradual. Roberto Viola, Director General of DG CONNECT, emphasised this at a Foresight Talk in Brussels in November 2024, highlighting how sovereignty and competitiveness are not mutually exclusive concepts and that there are no black-and-white solutions to the EU’s digitalization challenges. In this context, striking a balance between dependence and autonomy in technological solutions is essential for fostering a flourishing digital transformation.

Chips Act 2.0, being discussed now in Brussels, aims to build upon those initial foundations with sharper levers and greater clarity. Henna Virkkunen, Executive Vice-President of the European Commission is actively working on this crucial issue, although more concrete details have been slow to emerge since the announcement last April. There is also talk of a “sovereignty fund” to mobilise private capital alongside EU public money, plus enhanced coordination among member states to avoid duplication and to ensure scale. If designed and implemented well, Chips Act 2.0 could help Europe bridge the gap to its 2030 target, but its success will hinge on execution, regulatory coherence, and alignment among often-diverse national interests. It is hoped that an organisation such as the European Investment Fund will play a key role in stimulating private investment. The European Innovation Council, the only deep tech fund that actually finances semiconductors at high levels, needs to be strengthened in order to reach its full potential.

Furthermore, Europe has quietly been developing some of the most robust and forward-thinking tech companies in the world, as the continent aims to get a foothold in global tech markets and achieve some strategic direction in the fields of AI, quantum computing, supercomputing, IoT and semiconductor development. SiPearl, for example, is a French start-up that recently closed a €130 million Series A funding round, one of the largest in European semiconductor fabless history. The funds came from investors including the European Innovation Council Fund, Taiwanese Cathay Venture, and France 2030. Those funds are being used to develop the Rhea1 exascale processor for high-performance computing and AI applications (a processor set to be integrated into the JUPITER supercomputer in 2026).

CEO Philippe Notton has long been calling for the EU to step up in its support of European tech firms to shore up European sovereignty. “Our challenge is to remain an European company supported by the EU. We have a lot of ambition regarding the programmes such as EIC (European Innovation Council), EIC Step and EIC Scale-Up. EIC now has a worldwide reputation, and it is an important partner for the development of SiPearl,” he said.

At the same time, the rise of Mistral AI, a French AI start-up now valued at nearly $12 billion, with ASML investing €1.3 billion to become its top shareholder, highlights Europe’s ambition to play a sovereign role in critical technologies. Italian cybersecurity start-up Exein has also made headlines, raising €70 million in Series C funding earlier this year. Spanish company Multiverse Computing, the global leader in Quantum-inspired AI recently secured €215 million in Series B to scale its compression tool that reduces large language model size by up to 95% without sacrificing performance. More proof that Europe’s semiconductor and deep-tech ecosystem is more diverse and ambitious than often acknowledged.

Washington’s actions highlight need for a change of course

Notton’s calls for “true independence” make even more sense following the latest moves in the U.S. Senate. Europe cannot help but view this new semiconductor posture as contradictory. Washington is simultaneously pushing for Europe to buy billions of dollars in U.S. chips yet considering legislation that would force domestic chipmakers to prioritise internal customers, even at the expense of allied nations. This is a paradox that cannot function in real terms.

Such legislative ambiguity underscores, yet again, the urgent need for European strategic autonomy in critical sectors. Dependence on an "ally" whose priorities can abruptly shift from export promotion to protectionist first-rights entails severe risks. Ursula von der Leyen underlined this just recently when she stated that “we have seen how dependencies can be used against us. This is why we will massively invest in digital and clean tech.”

This investment is coming. Europe’s commitment via the Chips Act, its funding of smaller tech firms, and broader efforts to build a sovereign chip ecosystem all reflect a pragmatic response to this volatility. Having robust internal capacity in semiconductors is both a matter of industrial policy and a geopolitical imperative.

It remains to be seen if these moves in Washington stick despite widespread backlash, but Europe needs to be prepared for the worst.